Historical context: Rhodes at the height of its power

At the end of the 4th century BC, Rhodes experienced a spectacular boom. In 408 BC, the cities of Lindos, Ialysos and Camiros joined forces to found the city of Rhodes. From then on, the city became a central player in the Hellenistic world. Its strategic position between the Aegean Sea and the eastern Mediterranean enabled it to control routes linking Greece, Asia Minor, Ptolemaic Egypt and even Carthage.

Thanks to its powerful fleet, both commercial and military, Rhodes ensured maritime security. It fought piracy effectively and won the trust of neighboring kingdoms. Rhodes’ diplomacy was also on the rise. The city forged solid ties with the great powers of the time.

But that’s not all. Its modern port, naval arsenal, stable currency and school of rhetoric attracted thinkers, merchants and artists from all over the Mediterranean basin.

This prosperity supports ambitious projects. Town planning, culture, architecture: Rhodes shines on all fronts. In this climate of asserted power, the Colossus was born. This monument, far from being merely artistic, also became a political tool. It embodied the grandeur of the city and its determination to shine throughout the ancient world.

A prosperous city at the crossroads of trade

Rhodes quickly outgrew its military and symbolic role. It became a key economic center in the ancient world. Its well-sheltered, well-equipped port served as a strategic port of call for ships from Egypt, Syria, Asia Minor and Athens.

Thanks to a formidable war fleet, the city guarantees security in the Aegean. It effectively combated piracy, ensuring stable trade flows. This climate of trust encouraged a steady flow of merchants and precious goods.

Its warehouses overflowed with a variety of goods: wine and olive oil amphorae, fine ceramics, fabrics, oriental spices, rare metals and perfumes. This flourishing trade supported urban growth and cultural development. Authorities invested in the arts, sciences, infrastructure… and monuments.

At the same time, Rhodes established itself as a major intellectual center. Thinkers such as Hipparchus, the father of scientific astronomy, taught here. The city also attracted sculptors, architects and diplomats from all over the Hellenistic world.

The famous Rhodian maritime law, renowned for its rigor and fairness, still influences some of the foundations of international law today. In this atmosphere of innovation, prosperity and cultural influence, the foundations of the Colossus took shape. The project epitomizes the city’s artistic, religious and political ambitions.

A victory over Demetrios Poliorcetes

In 305 BC, Rhodes faced one of the most spectacular sieges in antiquity. Demetrios Poliorcetes, nicknamed “the taker of cities”, launched a major offensive against the city. Son of Antigonus the One-Eyed, this feared Macedonian general sought to force Rhodes to break its alliance with Ptolemy I, ruler of Egypt and his father’s strategic rival.

For over a year, the city withstood a methodical assault on an exceptional scale. Demetrios mobilized an imposing army, supported by a war fleet and an arsenal of sophisticated siege engines. His most famous machine: the Helipolis. This giant siege tower, some 40 meters high, was armored with iron plates, equipped with catapults, battering rams and mobile bridges. It is one of the masterpieces of Hellenistic military engineering.

Yet Rhodes held firm. Thanks to solid fortifications, exemplary organization and the courage of its inhabitants, the city held out. Figures such as Diagoras and Timachidas, general and strategist, effectively coordinated the defense. The spirit of cohesion, reinforced by a fierce determination to remain independent, played a decisive role.

In 304 BC, Demetrios had to abandon the siege. He reached an agreement and left the island. This victory, hailed throughout the Greek world, marked a historic turning point. To thank Helios, their tutelary god, the Rhodians decided to dedicate a gigantic statue to him. The Colossus of Rhodes became the symbol of their new-found independence, their faith and their collective power.

A city under the sign of Helios

Following their decisive victory over Demetrios Poliorcetes in 304 BC, the Rhodians attributed their salvation to Helios, the solar god they venerated as protector of the city. To celebrate their deliverance and assert their power in the Greek world, they decided to erect a monumental statue of him, visible from the sea, to honor his light and symbolize their new-found freedom.

This exceptional project, entirely financed by the sale of equipment abandoned by Demetrios’ army (war machines, weapons, bronze pieces), took on religious, artistic and political dimensions. In addition to being a votive offering, the Colossus of Rhodes became a striking declaration of sovereignty.

The figure of Helios, represented in anthropomorphic form, occupies a central place in Rhodian identity. It is engraved on numerous Hellenistic coins, including drachmas and tetradrachmas, depicting the god’s radiant face, often with spikes of light around the head. These coins served to spread the prestige of Rhodes far beyond its borders.

With this monument, the inhabitants inscribed their faith in stone and bronze, firmly anchoring the cult of Helios in the urban landscape and collective memory. The Colossus thus becomes the tangible embodiment of a resilient city, enlightened by the divinity it places at the pinnacle of its values.

The cultural and diplomatic golden age

Rhodes reached the height of its prosperity between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. Boosted by its commercial influence, it also became one of the most important diplomatic centers in the Hellenistic world. The island welcomed official delegations from Athens, Rome, Pergamon and Alexandria, consolidating its role as a geopolitical crossroads in the eastern Mediterranean.

In intellectual terms, Rhodes’ schools rivaled those of Athens and Alexandria. The city particularly distinguished itself in the fields of rhetoric, philosophy and law. Renowned orators and thinkers such as Panetius of Rhodes, one of the founders of Middle Stoicism, taught on the island. A disciple of Diogenes of Babylon, Panetius had a direct influence on Roman moral thought, notably through his exchanges with Scipio the African and Cicero.

Rhodes’ intellectual activity attracted students from all over the Greek world, and even from Rome. The prestige of its educational institutions further consolidated its image as an advanced city, combining economic power, political stability and cultural excellence.

A technical feat: how was the Colossus built?

Building the Colossus of Rhodes was one of the greatest engineering feats of antiquity. Erected between 292 and 280 B.C., this monumental statue dedicated to Helios stood some 33 metres high, the equivalent of a ten-storey building. Made of bronze cast on an iron and stone frame, it dominated the island of Rhodes, impressing visitors as soon as they arrived from the Aegean Sea.

The project mobilized major logistical resources, metal resources from all over the Mediterranean basin, and a specialized workforce. Architect Charès de Lindos, a pupil of Lysippe (Alexander the Great’s official sculptor), directed the work for over a decade. Although the statue was destroyed a few decades after its completion, the accounts of ancient authors such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder, as well as contemporary archaeological research, enable us to reconstruct the main stages of this exceptional achievement.

Even today, the Colossus is cited as a symbol of Greek technical and artistic mastery, and its construction fuels debate among historians, architects and engineers.

A spectacular construction serving a symbol

The project began shortly after Rhodes’ victory over Demetrios Poliorcetes, around 292 BC. To celebrate their new-found freedom, the Rhodians decided to honor Helios, their solar god. They therefore entrusted the creation of the Colossus to Charès de Lindos, a sculptor trained by Lysippe, Alexander the Great’s artist. This choice underlines a strong desire to create a work that is both monumental and deeply symbolic.

From the outset, the project took on an exceptional scale. It lasted almost twelve years. Hundreds of craftsmen from all over Greece were involved in the construction. Stonemasons, blacksmiths, carpenters and architects worked together on this collective adventure. It all began with the installation of a white marble base, several meters high, to ensure stability on rocky terrain.

Next, the builders create an internal structure of iron and stone blocks. This framework supports the weight of the beaten bronze cladding. Each plate, firmly riveted together, gradually forms an immense metal armour. To erect the whole without the aid of cranes, they build earthen ramps, climbing around the statue. In this way, they climb gradually, floor by floor.

When the Colossus reaches its final height, the mounds are dismantled, revealing the majestic silhouette of Helios. This process demonstrates the ingenuity of ancient Greek techniques. Despite the absence of modern machinery, the workers managed to create a structure capable of withstanding wind, sea air and even seismic tremors.

Ultimately, this project represents the pinnacle of Greek craftsmanship. It combines technical ingenuity, precision craftsmanship and political acumen, making the Colossus one of the greatest feats in the history of sculpture.

Absent plans, solid assumptions

No original plans for the Colossus have ever been found, which continues to fuel speculation. Ancient texts, notably those of Pliny the Elder, remain vague as to the processes used. As a result, researchers rely on technical comparisons and modern reconstructions to better understand the methods employed.

The majority of specialists agree that the statue was built by progressive elevation. Workers would have built earthen ramps around the statue, ascending floor by floor. With each step, a new layer of earth was added, facilitating access to the upper sections. This well-documented method had already been used for other monumental works, such as Athena Parthenos in Athens.

Two theories on structure and technical challenges

There are two main hypotheses concerning the installation of bronze plates. The first proposes direct on-site forging: the plates, molded from a wooden or clay model, were adjusted by hand, then attached to the framework with metal rivets or tenons. The second suggests the use of a temporary wooden framework, gradually replaced by stone blocks and iron, which were progressively integrated into the structure.

In both cases, weight distribution was a major challenge. The architects had to anticipate internal stresses, avoid subsidence and ensure stability in the face of sea winds. In addition, the salty humidity of the Aegean Sea increased the risk of corrosion. Finally, despite the absence of formal documents, these theories demonstrate rigorous planning and confirm the remarkable ingenuity of Rhodian craftsmen.

A victory turned into bronze: founding recycling

After the hasty departure of Demetrios Poliorcete, the Rhodians recovered a massive quantity of military equipment. Catapults, ballistas, siege towers and metal plates lay around the ramparts. Rather than storing or selling them, the city decided to make exceptional use of them.

The authorities chose to melt down these enemy weapons to finance and build the Colossus. This is not just a pragmatic choice. It conveys a powerful message: to transform the remnants of war into a symbol of peace, light and rebirth.

Each piece of weaponry becomes a fragment of the statue of Helios, the solar god of Rhodes. This decision illustrates a rare political intelligence: it links the memory of the conflict with the celebration of regained freedom. By exhibiting this recycled bronze in the form of a tutelary deity, the Rhodians are asserting their desire for peace through art.

Moreover, this strategic recycling means that the city doesn’t have to burden its finances. Instead of levying taxes or putting families into debt, it uses a “war chest” that has fallen from the sky. This exemplary management strengthens social cohesion and transforms the Colossus into a symbol of popular unity.

From then on, the statue became much more than an artistic masterpiece. It embodies a collective resilience, a reconquest of sovereignty through creation, and a diplomatic message addressed to the Hellenistic world. The Colossus is more than just a monument: it is the reflection of a civilization that chose light after trial.

A brutal end: the earthquake that brought down the giant

Rhodes, located at the junction of the African and Eurasian plates, has regularly suffered violent earthquakes since antiquity. At the time, the builders of the Colossus had no technology to absorb the tremors. The monument’s base, made of massive stone blocks, ensured basic stability, but remained vulnerable to geological hazards.

In 226 BC, a powerful earthquake struck the island. Historians, including Strabo, estimate its intensity at over 6 on the Richter scale. The port was damaged, walls collapsed, and the Colossus, despite its imposing stature, broke off at the knees. The impact twisted its internal iron structure, and the statue crashed, dislocated, to the ground.

This cataclysm marked the end of one of history’s greatest monuments. Yet far from being forgotten, the Colossus became part of legend. Out of superstition and at the behest of the Delphic oracle, the Rhodians decided not to rebuild it. They feared to defy the will of the gods by erecting such a colossal work once again.

This tragic episode reminds us that even the most ambitious masterpieces remain subject to the Earth’s natural power. It shows the limits of human ingenuity in the face of an unpredictable environment. The collapse of the Colossus, though accidental, adds a new facet to the myth: that of a glory that is shattered, but eternal in the memory of civilizations.

A bronze monument... gone too soon

Despite its imposing stature and symbolic significance, the Colossus of Rhodes only stood at the island’s port for around 66 years. Built around 292 BC, it collapsed in a major earthquake in 226 BC, just two generations later. This cataclysm not only destroyed one of the most impressive monuments in the ancient world, it also deprived subsequent generations of a unique testimony to Hellenistic virtuosity.

However, the Colossus’ untimely demise only added to its legend. Deprived of visible remains, travelers, chroniclers and artists kept the myth alive through fascinated accounts, idealized representations and sometimes extravagant hypotheses. From Pliny the Elder to Philostratus, ancient authors evoke a bronze giant lying on the ground, visible in pieces for centuries. Later Arab conquerors saw it as a source of wealth to be exploited.

Ultimately, it is the very absence of the Colossus that has contributed to its immortality. Its memory spans the centuries, carried by fantasy, legend and the prestigious status of “Sixth Wonder of the World”. Even today, it continues to intrigue historians, archaeologists and lovers of ancient heritage.

The earthquake of 226 B.C.

In 226 BC, a devastating earthquake struck the island of Rhodes, causing many buildings, temples and houses to collapse. This major earthquake, whose epicenter was probably located in the Aegean Sea, caused extensive material and human damage. The Colossus, a symbol of strength and grandeur, could not withstand the telluric power.

Its internal structure, made of iron and stone blocks, was weakened by repeated shaking. The breaking point was probably at knee level, causing the statue to collapse completely. The 30-metre-high work by Charès de Lindos crashed to the ground in pieces, marking the abrupt end of this architectural feat.

According to Plutarch, relaying older sources, the Rhodians then consulted the Delphic oracle, hoping to rebuild their monument. But the oracle was firmly opposed, believing that the gods had manifested their will. Fearing to offend Helios, the inhabitants gave up the idea of raising the statue.

Despite its ruined state, the Colossus remained a site of admiration for almost 900 years. Travellers from all over the Mediterranean world describe the bronze pieces lying on the ground, some of whose fingers are said to be larger than a man. Although broken, this vestige continues to arouse fascination and respect.

A tragic end under the Arab Empire

In 653 A.D., the island of Rhodes fell to the troops of the Umayyad caliphate, led by general Mu’awiya, the future caliph. During this invasion, the soldiers discovered the monumental remains of the Colossus of Rhodes, which had been lying on the ground for several centuries. Although the statue has been in ruins since the earthquake of 226 BC, its bronze fragments are still impressive.

According to Theophanes the Confessor, a 9th-century Byzantine chronicler, the Arabs decided to dismantle the remaining pieces of the statue for profit. The bronze plates, probably still numerous and intact, were sold to a Jewish merchant in Syria. Legend has it that these fragments were transported on 900 camels to Emesa (now Homs), where they were melted down and resold as raw metal.

Although some of the details are undoubtedly narrative embellishments, this story marks the definitive end of the Colossus, handed over to looting and commercial exploitation. Nothing remains of the giant of Helios, whose bronze, once a symbol of triumph, is now melted down for unknown uses.

This episode highlights the transition from an ancient world to a new geopolitical order, in which the great works of Greek history lose their symbolic value in favor of economic or military considerations.

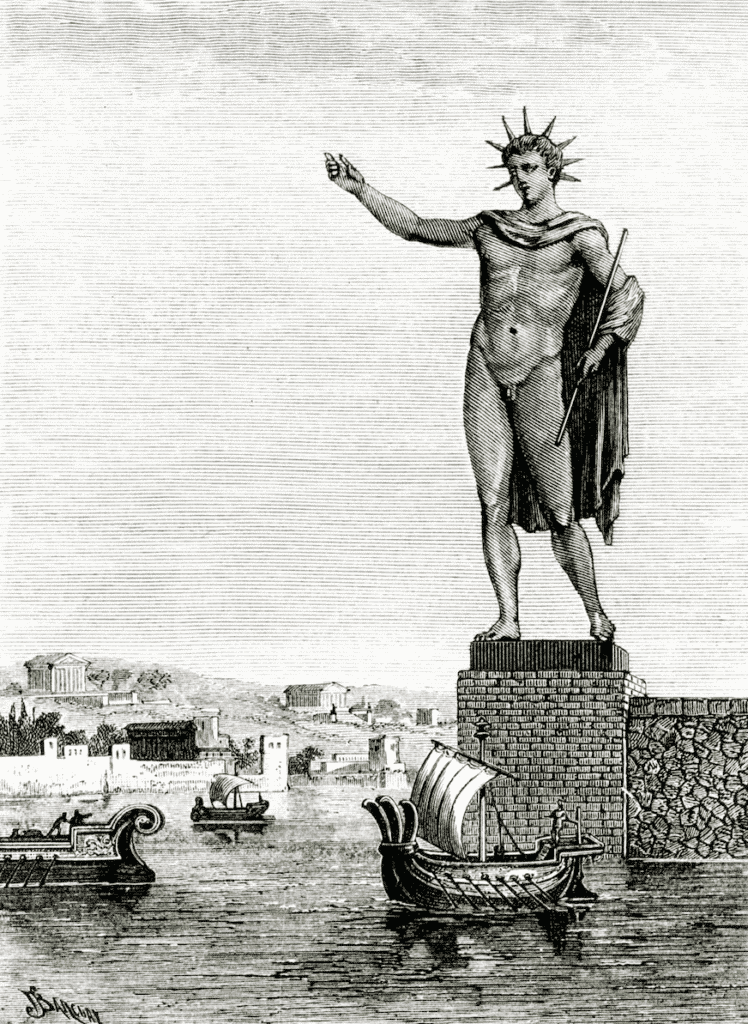

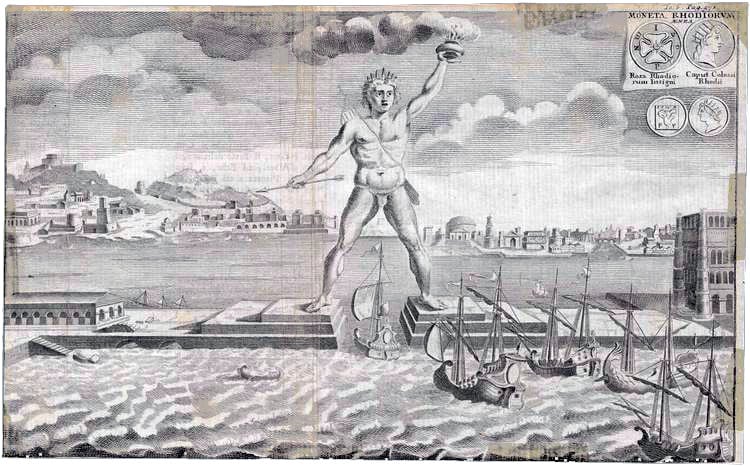

The false image of the "harbor keeper": a persistent medieval invention

Contrary to popular belief, the Colossus of Rhodes did not stand with his legs apart at the entrance to the port. This spectacular vision of ships passing between his legs only appeared in the Middle Ages. It is the result of fantasized European illustrations, influenced by Gothic engravings and Western travelers’ accounts.

Ancient sources, however, never mention such a posture. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, speaks of a statue lying down after the earthquake, but does not describe its initial position. Nor does Strabo mention anything of the sort. This confirms that the myth of the Colossus straddling the harbour is a late construction, with no solid historical basis.

From a technical point of view, such a position would have been unfeasible in Hellenistic times. A statue over 30 metres high, resting on two points so far apart, would have been unstable. In a seismically active region like the Aegean, it would have been architecturally suicidal.

Today, experts believe that the statue stood further back, probably near the sanctuary of Helios or the agora. This central position, on a massive plinth, placed the Colossus at the heart of the city’s religious and political life, and guaranteed it optimum stability.

Nevertheless, this false representation has fed the collective imagination for centuries. It continues to fuel films, comics, video games and postcards. Paradoxically, this discrepancy between myth and reality reinforces the legendary dimension of the Colossus of Rhodes.

A presence intact despite his fall

The destruction of the Colossus of Rhodes marks more than just the loss of a monument. It profoundly affected the city, both symbolically and in terms of its identity. Considered the pride of Rhodes and a dazzling tribute to Helios, the solar god, its fall in 226 BC marked the end of a golden age and left the population in a state of stupefaction mingled with resignation.

Yet far from being forgotten, the ruins of the Colossus soon became a major attraction. Several ancient authors, including Strabo and Pliny the Elder, report that visitors came expressly to contemplate the monumental remains of the statue lying on the ground. The sheer size of the bronze fingers and arms was awe-inspiring, revealing the sheer size of the original work.

These remains continue to fuel the collective imagination. Even shattered, the Colossus remains an icon of Greek ingenuity and Rhodian power. The idea that greatness survives destruction is gradually asserting itself as a universal message.

Indeed, the fallen Colossus continues to symbolize a radiant city, whose cultural, economic and artistic influence far exceeds its geographical size. This memory, handed down through the centuries, confirms the Colossus’ lasting impact on the history of the ancient world.

The Colossus of Rhodes: a legend among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Although the Colossus of Rhodes only existed for a little over fifty years, it remains one of the major symbols of Antiquity. Listed as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, it stands alongside such mythical monuments as the Pyramids of Giza and the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Its impressive height of around 33 metres and its bronze structure represented a unique feat for its time.

What makes the Colossus so exceptional goes beyond its size. It was built in a particular context: a free, victorious city determined to assert its independence. The statue stood as a visual statement, both political and spiritual, paying homage to the god Helios.

Its strength also lay in the balance between technical prowess, symbolic power and cultural influence. This alchemy forged its renown. Surprisingly, its early collapse following an earthquake did nothing to tarnish its legend. On the contrary, its disappearance nurtured its mysterious aura.

Since then, the image of the Colossus has continued to fascinate. It has inspired generations of artists, travellers and historians. Even today, it embodies the grandeur of ancient civilizations and the creative force of humanity.

What remains of the Colossus today?

Although the Colossus of Rhodes disappeared nearly two millennia ago, its cultural and symbolic imprint remains deeply rooted in the collective memory. To date, no physical remains have been found: neither bronze fragments nor a base that can be identified with certainty. Yet, the solar giant continues to shine through the ages, carried by ancient accounts, the writings of historians such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder, and the many artistic representations from the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Today, the island of Rhodes perpetuates the memory of its mythical monument through references in public spaces, contemporary sculptures, exhibitions and tourist circuits. The port of Mandraki, although not confirmed as the original site, is often associated with the Colossus, attracting thousands of visitors every year. Two modern statues of fallow deer, symbols of the town, mark the entrance to the port and keep the popular legend alive.

The Colossus now embodies the Rhodian identity, a heritage of grandeur, resilience and influence. It also inspires contemporary reconstruction and memorial projects, albeit controversial ones. Although it doesn’t exist physically, the Colossus lives on in the world’s collective imagination. It is one of those rare monuments whose absence nourishes mystery even more than its presence, becoming a universal founding myth at the crossroads of history, archaeology and dreams.

No trace found, but a memory intact

To date, no confirmed archaeological remains of the Colossus of Rhodes have been discovered. No base, bronze fragments or identifiable structural elements have been found. Excavations around the port of Mandraki and the ancient acropolis have revealed no formal clues. Some researchers suggest that the bronze was completely recovered, melted down and then dispersed, making it virtually impossible to locate.

Despite its physical absence, the memory of the Colossus lives on in ancient accounts. Authors such as Strabo, Pliny the Elder and Philostratus describe its dimensions, posture and supposed location. Even if their texts sometimes date from centuries after its fall, they remain the main source for understanding this ancient marvel.

The myth endures. In popular culture, the Colossus still inspires. It can be found in literature, the visual arts, cinema and even video games. It’s a fascinating paradox: one of the best-known statues of Antiquity, yet totally extinct. In Rhodes, its legacy remains palpable. Street names, monuments and local businesses perpetuate its image. The spirit of the Colossus continues to shape the island’s identity.

A bold idea to revive the Colossus of Rhodes

In the early 2000s, a group of European architects launched an ambitious project to rebuild the Colossus of Rhodes. One of the best-known architects, the German Gert Hof, a specialist in monumental installations, soon joined the initiative. Their aim was not to copy the ancient statue, but to propose a modern, lasting and meaningful work of art.

The idea was a powerful one. This new version of the Colossus was to exceed 150 metres in height, five times higher than the original. Designed using contemporary materials such as steel and glass, the structure was also to incorporate solar panels. The project also included a library, a cultural gallery and a research center on ancient wonders.

The architects plan to erect the statue at the entrance to Mandraki harbour. Legend has it that this is where the old statue once stood, although historians have little agreement on this hypothesis.

For a short time, the project aroused enthusiasm. Greek and German media reported on the initiative, which also attracted the attention of the general public. But difficulties soon arose. The cost, estimated at over 250 million euros, seemed unrealistic for an island facing economic challenges. What’s more, the lack of consensus on what the Colossus should look like slowed down support.

Despite the passion of those behind the project, the idea was abandoned. Yet it left its mark. The mention of a new Colossus is enough to stir the imagination. Rhodes, still deprived of its Ancient Wonder, continues to inspire. The debate between remembering the past and looking to the future remains open.

In the footsteps of the Colossus: what can you visit today?

To date, no official archaeological site has been certified as the exact location of the Colossus of Rhodes. However, several areas of the island have attracted the attention of historians, archaeologists and keen visitors alike.

The first, and most popular, is located at the entrance to the port of Mandraki, where two columns topped by statues of a stag and a hind – the town’s emblems – symbolically mark the presumed site where the giant once stood. Although romantic, this depiction is based more on medieval tradition than on reliable ancient sources.

A second, more recent hypothesis places the Colossus on the heights of the city, near the ancient acropolis of Rhodes, close to the sanctuary of Helios. This more geologically stable area would have been better suited to erecting a structure of this scale. Some researchers consider this version to be more plausible from a technical point of view, although no material evidence has yet been found.

Finally, to gain a better understanding of the historical, cultural and artistic context of the Hellenistic period, a visit to the Rhodes Archaeological Museum, housed in the former Knights’ Hospital, is highly recommended. This museum features a rich collection of sculptures, inscriptions, votive objects and mosaics from all over the island, providing essential insights into the environment in which the Colossus was conceived.

A living myth in Rhodian culture

Although no physical trace of the Colossus remains, his legacy is still very much alive in Rhodes. Everywhere on the island, stylized representations flourish in public spaces. These include modern statues, mural frescoes, decorative mosaics and various ornamental sculptures. All are reminders of the solar giant’s vanished grandeur.

Her effigy is also used in a wide range of visual media. It can be found on commemorative coins, stamps, cultural posters and tourist brochures. It also appears on the logos of local institutions. Thanks to this omnipresent iconography, Rhodes’ visual identity is strengthened and clearly expresses its attachment to this Wonder of Antiquity.

In addition, public gardens sometimes feature statues inspired by the Colossus. They remind walkers of the city’s glorious past. This artistic presence helps to maintain the collective memory while cultivating lasting local pride.

Finally, although absent from archaeological sites, the Colossus never really disappears. It continues to exist in the consciousness of its inhabitants, in the tourist imagination and in everyday culture. Rhodes perpetuates its myth by integrating it into its modern life and brand image.

A heritage passed on through education and culture

Even today, the Colossus of Rhodes plays an important role in Greek education. It is a regular feature of school curricula, particularly in history, civics and ancient culture classes. Students learn about its historical context, symbolic significance and the technical prowess of its construction, making it an excellent teaching aid for understanding the values and ambitions of the Hellenistic world.

Beyond the classroom, a number of temporary exhibitions in Greece and Europe showcased the history of the Colossus. Museums of archaeology, art history and ancient engineering presented models, digital reconstructions and objects illustrating the period. of its construction. These events reinforce the cultural transmission of this emblematic figure.

Finally, the Colossus is often mobilized in contemporary debates on monumental art, the political role of statues and vanished construction techniques. It is an essential reference for historians, teachers and curators, who use it as an anchor to evoke the great achievements of the past and their resonance in the modern world.

The Colossus of Rhodes, a pillar of cultural tourism

Even without archaeological remains, the Colossus of Rhodes remains a mainstay of local tourism. Every year, thousands of visitors scour the old town in search of clues to this vanished marvel. Thanks to guided tours in several languages, everyone can discover its history, its construction and its fall with passion.

In addition to these routes, numerous explanatory panels line the historic center. At the Mandraki harbour or near the Saint-Nicolas jetty, they present various theories on the location of the Colossus. In this way, visitors can better visualize its gigantic size while exploring the heritage of the Rhone.

At the same time, retailers play an essential role in passing on this myth. Many stores sold bronze statuettes, postcards, T-shirts and magnets depicting the solar giant. Thanks to this distribution, the image of the Colossus became part of the collective imagination and reinforced the island’s visual identity.

Tourist offices and travel agencies are also making the most of this heritage. They include the story of the Colossus in their cultural tours. Some go even further, offering themed cruises or dedicated conferences. In this way, the Colossus continues to captivate curious travellers with a passion for history.

The Colossus of Rhodes: a timeless legacy

Gone for over two millennia, the Colossus of Rhodes remains a global cultural icon. Thanks to its monumental stature, its message of resilience and its symbolic significance, it continues to make a lasting impression. Listed as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, it fully embodies the ingenuity and technical daring of ancient civilizations.

Over time, its image has fed the collective imagination. It has inspired painters, writers, architects and filmmakers throughout the ages. From medieval manuscripts to contemporary digital creations, the Colossus has become the archetypal giant protector. Even when it has collapsed, it is still remembered, somewhere between fiction and historical reality.

Even today, its influence extends far beyond the borders of Rhodes. It can be found in school textbooks, popular culture objects and futuristic architectural projects. In this sense, the Colossus proves that heritage can survive without stone or metal, as long as it lives on in people’s stories, symbols and consciousness.

The Colossus of Rhodes in the artistic and literary imagination

Although no archaeological remains have survived, the Colossus of Rhodes has had a profound influence on the history of art and literature. As early as Roman times, authors such as Pliny the Elder and Strabo evoked this titanic statue, attempting to describe its posture, materials and symbolic role within the city. Their fascination nurtured the first literary representations of a monument that had already become mythical.

Over the centuries, this fascination has never waned. Renaissance poets, neoclassical artists and Grand Tour travelers all made the image of the Colossus their own. They incorporated it into stories exalting the lost grandeur of Antiquity, often reinterpreting it according to the tastes of their time.

It was in the 19th century in particular that the iconographic myth took hold. Engravers, influenced by orientalism and archaeological rediscoveries, spread the spectacular image of a Colossus straddling the entrance to Rhodes harbor, its feet resting on two opposite quays. Although technically unrealistic, this vision had a lasting impact on the Western imagination.

Even today, this representation continues to inspire illustrators, comic strip authors, video game designers and film directors. It illustrates the power of a symbol capable of transcending the centuries, even in the absence of any material trace.

The Colossus, a timeless symbol of power and identity

Far beyond its physical stature or technical prowess, the Colossus of Rhodes embodies universal values. Resilience in the face of hardship, victory over invaders, assertion of fierce independence: the statue not only celebrated a god, but also conveyed the collective ambition of a people. It crystallized the image of a flourishing city, capable of rising from siege to take its place in the Mediterranean world.

These ideals have stood the test of time. In the collective imagination, the Colossus has become the symbol of a bygone but still admired ancient grandeur. Even today, it inspires discourses on strength, freedom and cultural resilience. This memorial role is reinforced by the constant presence of his name in everyday life in Rhodes.

In terms of tourism and culture, the Colossus’ imprint is omnipresent. Hotels, restaurants and cafés, as well as artistic and sporting events, all take advantage of the island’s prestigious heritage. Establishments such as the Colossus Hotel, themed festivals and merchandising play on this ancient reputation to attract visitors and revive the local memory.

So, even without material existence, the Colossus remains a living emblem. It is the embodiment of Rhodian pride, helping to forge a strong cultural identity between glorious past and contemporary influence.

A cultural icon in the visual arts and modern fiction

The legend of the Colossus of Rhodes goes far beyond ancient history. For centuries, this monumental statue has inspired artists, filmmakers, authors and creators of fictional universes. Although no longer in existence, its silhouette remains one of the most evocative symbols of Greek grandeur.

Sergio Leone’s “The Colossus of Rhodes ” (1961) is the most emblematic of these films. Although historically romanticized, this peplum has left a lasting impression on the collective imagination. It helped anchor the idea of a protective statue dominating the port, popularizing a now-familiar, if erroneous, representation.

In the world of video games, the figure of the Colossus continues to fascinate. Titles such as Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, which immerse players in ancient Greece, regularly incorporate indirect references to the statue. Even when the statue is physically absent, its influence is felt in dialogues, quests and frescoes throughout the game.

Comics and children’s literature are not to be outdone. The Colossus appears in a number of albums inspired by Greek mythology or ancient adventures, often as a spectacular backdrop or the starting point for a puzzle. This treatment helps to pass on the legend to new generations.

In short, the Colossus of Rhodes has never ceased to live on in popular culture. Its presence in modern works, though sometimes distorted, keeps alive the aura of a vanished monument that has become immortal in stories.

An icon revisited through design and digital technology

Today, the Colossus of Rhodes continues to exist, thanks to digital technologies and the creativity of contemporary artists. It is enjoying a veritable virtual renaissance, fascinating history buffs and the general public alike.

On the one hand, 3D reconstructions are opening up new perspectives. Several specialized studios, often in collaboration with museums or university institutes, have developed digital models of the Colossus based on ancient descriptions by Pliny the Elder or Strabo. These projects enable immersive visualization of the statue, particularly in virtual reality. In addition, some applications offer interactive tours of ancient Rhodes, where the Colossus is returned to its original position in a recreated environment.

On the other hand, contemporary artists freely reinterpret his image. In urban installations, monumental graffiti or graphic animations, the figure of the Colossus becomes a medium of expression. Sometimes a symbol of forgotten grandeur, sometimes a metaphor for collapse or collective memory, he adapts to current themes such as excess, heritage or the fragility of civilizations.

In short, the Colossus never stops evolving. Thanks to art and technology, it continues to fuel the collective imagination. No longer a mere ruin, but a revisited, living, engaged figure, part of the cultural and social issues of our time.

The Colossus of Rhodes and other wonders of the ancient world

The Colossus of Rhodes didn’t just shine for its size or local symbolism. As the last of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World to be erected, it occupied a special place in the collective imagination. This section compares it with the other wonders to better understand its historical, technical and symbolic significance, and why it continues to fascinate millennia after its disappearance.

A late but revolutionary work among wonders

Unlike the Pyramid of Cheops, built around 2560 BC, or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, whose existence in the 6th century BC is still debated, the Colossus of Rhodes was built much later, between 292 and 280 BC, during the Hellenistic period. This chronological difference underlines not only the spectacular evolution of construction techniques over the centuries, but also the transition to a new artistic era: that of symbolic gigantism.

At 33 metres high and with a structure combining stone, iron and bronze, the Colossus was the largest metal statue ever produced in Antiquity.. While the Alexandria lighthouse ( also completed around -280 ) met a utilitarian need for navigation, and Babylonian gardens evoked contemplative luxury, the Colossus embodied a powerful political and religious message.. He celebrated Rhodes’ victory over Demetrios Poliorcete and glorified the cult ofHeliosgod of the sun. It was a a manifestation of freedom, independence and civic faith, at the heart of Rhodian identity.

A posterity intact despite a fleeting existence

Although the Colossus of Rhodes collapsed only 56 years after its construction in the earthquake of 226 BC, it remains one of the world’s most famous wonders. Its memory far exceeds that of other prestigious monuments such as the statue of Zeus in Olympia or the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. These majestic masterpieces, however, have not left such a lasting impression on popular culture.

This difference can be explained. Where other Wonders served local cults or imperial figures, the Colossus carried a universal message. It represented light triumphing over darkness, peace regained after hardship, and the resilience of a people. These timeless values still resonate today.

Its rapid collapse has not diminished its influence, quite the contrary. The absence of remains has fed the collective imagination. Illustrators, writers and film-makers have been free to reinvent it, reinforcing its mystical aura. This artistic freedom has enabled the legend to live on through the centuries without ever dying out.

The Colossus, civic symbol of the Hellenistic world

The Colossus of Rhodes was more than just a bronze statue. First and foremost, it represented the high ideals of the Hellenistic Greek world: freedom, civic unity and resistance to oppression. Unlike the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, it honored neither prince nor contemplation. It embodied a strong political message.

Dedicated to Helios, the solar god and protector of the island, the statue celebrated the Rhodian victory over Demetrios Poliorcetes in 304 BC. It affirmed the pride of a united people, determined to defend its independence against the great powers of the time. The choice of bronze, solid and visible from the sea, reinforced this statement.

This commemorative role is reminiscent of that of Athena Parthenos, sculpted by Phidias for Athens. Yet the Colossus went further. Its outward appearance was aimed at citizens and travellers alike. It displayed Rhodes’ maritime power and the vitality of its democratic values.

In short, it was a profoundly civic work, far more than a simple artistic feat. It integrated perfectly with the cultural codes of the Greek world, while conveying a clear message to the entire Mediterranean basin.

The Colossus in ancient accounts and historians' writings

Despite its early demise, the Colossus of Rhodes continues to fascinate thanks to the writings of antiquity. In the absence of physical remains, it is the testimonies of ancient authors such as Pliny the Elder, Strabo and Philo of Byzantium that nourish our understanding of this marvel. Their descriptions, often rich in detail, allow us to imagine the size, posture and symbolic function of this monumental statue. This section looks back at the most significant historical sources, analyzing what they reveal – or leave in the dark – about the Colossus of Rhodes, a masterpiece of the Hellenistic period.

Mentioned as early as the 3rd century B.C.

As soon as it was completed around 280 BC, the Colossus of Rhodes attracted the attention of Greek intellectuals. Philo of Byzantium, an engineer of the IIIᵉ century BC, ranked it among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. This early classification underlines the admiration this monumental work was already arousing throughout the Mediterranean basin.

Few of Philo’s texts have survived, but his list remains a reference. Other, less famous Greek authors also mention the colossal construction site and pay tribute to Charès of Lindos, a renowned sculptor trained by Lysippus. All emphasize the technical prowess, precision of detail and fascination of visitors.

Even if the sources are sometimes fragmentary or reported by later compilers, they all converge on the same observation. As soon as it was built, the Colossus aroused great enthusiasm throughout the Hellenistic world. It was not only a tribute to Helios, but also a masterpiece immediately recognized as such.

Strabo and Pliny the Elder: invaluable testimonies

Of all the rare accounts of the Colossus of Rhodes, Strabo’s remains essential. This 1st-century BC geographer briefly mentions the statue in his Geographyemphasizing its symbolic role in the island’s landscape. By his time, the Colossus had already been destroyed, which explains his relative silence on its exact form. This lack of detail has only amplified the mystery surrounding its position and location.

Pliny the Elder offers a more precise description in his Natural History (Book 34, paragraph 18). He indicates that the statue reached 70 Roman cubits, or around 33 meters. This made it one of the tallest sculptures of antiquity. He also describes the ruins still visible, evoking gigantic limbs scattered across the ground. Their sheer size was enough to amaze visitors. Pliny adds that a single finger of the Colossus required several men to encircle it.

Although these accounts date from after the statue’s collapse, they remain essential. They shed light on its dimensions, its visual impact and the fascination it still exerted centuries later. These accounts have enabled the Colossus to stand the test of time and remain present in our collective memory.

A fascination that goes beyond the Roman Empire

Even after its fall in 226 B.C., the Colossus of Rhodes never disappeared from history. On the contrary, its presence continues to leave its mark on people’s minds, particularly those of Roman travellers and pilgrims from the East crossing the Mediterranean. These visitors, fascinated by the monumental ruins of the statue, spoke of it as an unequalled testimony to Hellenistic grandeur.

Accounts often mention the Colossus’ prone head, scattered hands or massive feet, lying on the ground in an imposing posture. The mere sight of these fragments impresses witnesses, so much so that they describe him as still alive in his decay. Several authors point out that the Colossus, even on the ground, arouses as much admiration as if he were still standing.

This evocative power, passed down from generation to generation, helps forge the myth surrounding the monument. It becomes a symbol not only of the fragility of human greatness, but also of the memory of ancient civilizations. It is largely thanks to this continuing fascination that the Colossus retains its place among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, long after its physical demise.

References as far back as Byzantium

During the Byzantine era, the Colossus of Rhodes continued to fuel historical accounts. Authors cited the statue in encyclopedic texts and compilations of ancient sources. Over the centuries, however, memories gradually fade. The absence of archaeological remains and direct testimonies encourages confusion.

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, in the 10th century, still refers to the Colossus in his writings on imperial administration and the wonders of the world. He presents it as a masterpiece of Greek ingenuity. However, the descriptions become blurred. Sources diverge on its location: some place it in the center of the port, others near the acropolis or in a sanctuary dedicated to Helios.

These uncertainties gave rise to new interpretations. Little by little, medieval accounts were added to the legend, often far removed from historical reality. This vagueness reinforced the mystery surrounding the Colossus and prolonged its presence in the collective imagination.

The Colossus of Rhodes in the modern imagination

Even when destroyed, the Colossus of Rhodes continues to inspire artists and designers. Its image of a bronze giant watching over an island city remains deeply rooted in people’s minds. It embodies grandeur, mystery and resilience. From the Renaissance onwards, many European scholars sought to give it new form, often through idealized representations.

Subsequently, it was in the XIXᵉ century that his figure spread widely. The Colossus becomes a major motif in popular iconography. He appears at the crossroads of fiction, myth and historical reconstruction. Thanks to this growing visibility, his aura took root in the collective imagination.

Even today, her mythical silhouette appears in a wide range of media. We find her in films, video games, comic strips and historical novels. Whether faithful to reality or entirely fantasized, this figure continues to fuel tales of antiquity and human achievement.

This constant presence reinforces the myth’s evocative power. It shapes our perception of the past, while reminding us of the enduring influence of Greek culture. Invisible yet omnipresent, the Colossus remains one of the most powerful symbols of ancient history.

From works of art to ancient literature

From antiquity to the present day, the Colossus of Rhodes has never ceased to inspire creative minds. In antiquity, authors such as Apollonius of Rhodes, famous for his epic The Argonautics, were already evoking the wonders of the eastern Mediterranean, even if his mentions of the Colossus remain indirect. Lucian of Samosata, famous for his satirical texts of the 2nd century AD, refers to the fascination that the statue still aroused, even though it had already collapsed centuries earlier.

From the Renaissance onwards, and with the rise of European Romanticism, the Colossus became a symbol of vanished grandeur. Poets and writers saw it as a metaphor for an idealized ancient world. Contemporary authors such as Jean-Pierre Vernant and Marguerite Yourcenar, in their reflections on the Greek past, evoke the mythical significance of the Colossus as a witness to a bygone golden age. Nineteenth-century illustrators, engravers and painters – notably in school textbooks and travelogues – often depicted him straddling the harbor, popularizing an erroneous but iconic image.

Hollywood and series: a monument reinvented

Even today, the entertainment industry continues to draw on the image of the Colossus of Rhodes to represent past greatness. It also uses it to illustrate the fragility of civilizations in the face of time. In the film Jason and the Argonauts (1963), directed by Don Chaffey, a huge animated statue clearly recalls the Colossus. Although this scene is historically inaccurate, it has acquired a cult following. As a result, it reinforced the image of the bronze giant in popular culture.

In addition, the series Game of Thrones (HBO) also uses this inspiration. The imaginary city of Braavos features a colossal statue at the entrance to its port. The statue is directly inspired by medieval depictions of the Colossus straddling the port of Mandraki. Thanks to this visual wink, the series perfectly illustrates how myth still feeds the collective imagination, even in entirely fictional universes.

More generally, in contemporary audiovisual productions, the Colossus often symbolizes the inordinate power and inevitable fall of empires. He represents a meeting point between history and legend. That’s why its image remains one of the strongest of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. It continues to fascinate, both on screen and in the most grandiose of modern narratives.

The Colossus of Rhodes in games, comics and collectibles

The Colossus of Rhodes continues to inspire many interactive and visual media. In Assassin’s Creed Odyssey (Ubisoft, 2018), although physically absent from the game – since it had disappeared by the time of the script – its influence remains palpable. Numerous references evoke ancient wonders, including the Colossus, and recall its symbolic role in the history of Rhodes. The player evolves in a world rich in myths and monuments inspired by Greek masterpieces.

In the world of comics, the silhouette of the Colossus is a frequent sight. It can be found in graphic series dedicated to Antiquity, where it serves as a majestic backdrop. It symbolizes Hellenistic power, technical mastery and the collective will of a people.

His image is not limited to fiction. The Colossus also appears in numismatics and philately. Collector’s coins, stamps and commemorative banknotes still depict it today. Greece and several other European countries are celebrating this vanished monument by dedicating lasting, accessible media to it.

Thanks to this constant diffusion, the Colossus has become a reference figure. He is just as much a part of geek culture as he is of artistic and educational circles. The myth of the Colossus lives on, proving his universal appeal and his anchorage in the collective imagination.

The Colossus in contemporary debate: should it be rebuilt?

The myth of the Colossus is not limited to a legacy frozen in time. Since the 1960s, the idea oferecting a new version of this monumental statue has regularly resurfaced. The idea is as enthusiastic as it is controversial. While some see it as a legitimate tribute to Rhodian history and a powerful lever for tourism, others question the historical relevance and cultural implications of such a project.

This desire for resurrection is based not only on nostalgia, but also on a contemporary desire to reconnect with the strong symbols of Greek heritage. Several proposals were put forward by international architects, particularly after 2008, ranging from a modernized Colossus with an ecological vocation to a multifunctional public work of art. However, budgetary obstacles, archaeological uncertainties about the original site, and the ethical issues involved in rebuilding a vanished icon are holding up any concrete realization.

This debate is fascinating researchers, citizens, local councillors and heritage experts. It raises essential questions: is it possible to recreate a wonder of the world? And if so, for what purpose – to commemorate, to educate, or simply to attract crowds? This dialogue between past and present is an integral part of the evocative power that the Colossus of Rhodes retains to this day.

Ambitious but controversial projects

Since the 2000s, several Greek and European architects have proposed reconstruction plans. In 2015, a collective of German and Greek architects presented a modern project 150 meters high, integrating museum, exhibition space and lighthouse. This symbolic and technological project never saw the light of day, however, due to its estimated cost of over 250 million euros.

Why rebuild? A vision between memory and future

Those in favor of reconstruction advocate a visionary heritage project, at the crossroads of ancient memory and modern innovation. For them, resurrecting the Colossus would put Rhodes back on the international stage as the guardian of a universal heritage.

From a cultural point of view, such an initiative would reaffirm the importance of the Hellenistic world in human history. It would also be a tribute to Greek technical ingenuity, while promoting an educational approach aimed at younger generations.

The economic benefits would be considerable. Millions of visitors could flock here every year, boosting tourism, employment and local investment. Some believe that the mere announcement of a project of this scale would be enough to reposition the island as one of the must-visit destinations in the Mediterranean basin.

Finally, the project’s supporters see it as a symbol of resilience for contemporary Greece: transforming a past glory into an engine for the future, just as the Colossus represented for the Rhodians of antiquity.

Archaeological reserves and ethical issues

Despite the enthusiasm surrounding these projects, a large part of the archaeological community remains opposed to the idea of reconstructing the Colossus. For researchers and historians alike, there are a number of fundamental reasons why such an undertaking is scientifically questionable.

Firstly, the exact location of the statue has never been identified with any certainty, despite the hypotheses put forward since the 19th century. Some imagine it near the ancient agora, others at the entrance to the port of Mandraki. No archaeological excavation has uncovered a base, foundations or fragments of the original structure. Any reconstruction would therefore run the risk of being totally speculative, disconnected from material and historical data.

Secondly, critics point out that the Colossus was not an entertainment monument, but a major religious offering dedicated to Helios, symbolizing resilience and victory. A contemporary 150-metre reconstruction, with its high-tech theme park allure, could distort the original intention of the work, to the benefit of a commercial logic.

Finally, many experts fear that this type of project will overshadow the authentic remains of the island of Rhodes, whose medieval heritage has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1988. In their view, the memory of the Colossus should remain in the realm of history, research and education, rather than that of approximate reproduction.

The artistic legacy of the Colossus of Rhodes

Much more than a feat of engineering, the Colossus of Rhodes has left a lasting imprint on the history of art. Its scale, posture and symbolism have inspired generations of sculptors, architects and thinkers, from Antiquity to the present day. This section explores in depth his influence on monumental sculpture, from Hellenistic statues to 19th-century neoclassical projects, and modern works such as the Statue of Liberty, often referred to as a spiritual heir to the bronze giant. A fascinating artistic trajectory, where technique, aesthetics and ideology intersect.

The legacy of Hellenistic realism: the immediate artistic impact

The Colossus of Rhodes represents the apogee of the Hellenistic school of sculptural realism. Built around 292 BC, it symbolizes the transition from the idealized forms of Greek classicism to more expressive, monumental representations. Inspired by statues of Zeus at Olympia or Athena Parthenos, it pushes the boundaries of sculpture with its colossal proportions, while maintaining a realistic posture and rendering.

His style had a profound influence on the statuary of the time, particularly in Asia Minor, Ptolemaic Egypt and Pergamon, where artists took up this monumental style to glorify deities or rulers. The choice of depicting Helios with human features, in a solemn yet accessible posture, redefined the way gods were sculpted in public spaces.

The Colossus revisited by modern and contemporary artists

Over the centuries, the Colossus of Rhodes has fed the imagination of artists far beyond antiquity. From the 19th century onwards, painters such as Gustave Moreau seized on its imposing silhouette to explore themes of myth, power and decadence. His symbolist style transformed the figure of the colossus into a visual allegory, both divine and tragic.

In the 20th century, Salvador Dalí also drew inspiration from the monument’s excess to illustrate the tension between dream, memory and fall. In his Surrealist works, the evocation of a collapsed giant becomes the reflection of a humanity losing its bearings.

More recently, contemporary architects and urban planners have drawn inspiration from this figure for visionary projects. The posture of the titanic man dominating the landscape has become a powerful architectural motif, sometimes evoking the grandeur of past civilizations, sometimes the vanity of human ambition.

A figure reinterpreted in contemporary art

Although rooted in history, the Colossus of Rhodes continues to inspire contemporary artistic creation. Numerous artists reinterpret it to question modern themes such as collective memory, the fragility of power and the legacy of civilizations. Its image becomes a critical tool, far from a simple, fixed homage.

In some modern art biennials or digital exhibitions, silhouettes of the Colossus are projected in large format. Sometimes fragmented or deconstructed, they symbolize the collapse of empires and the traces left in history. These works offer a fresh look at Antiquity and its emblematic figures.

Visual artists have also hijacked its posture, its shape or its gaze turned towards the sun. They use it to evoke contemporary issues, such as colonial domination or the recuperation of ancient symbols in mass culture. Through these performances and installations, the Colossus rediscovers a political and poetic dimension.

These creations prove one essential thing: the Colossus evolves with the times. It crosses artistic currents, transforms itself as visions change, and remains a powerful universal symbol of grandeur, fall and rebirth.

Was the Colossus the origin of the Statue of Liberty?

Although there is no historical evidence of a direct link between the Colossus of Rhodes and the Statue of Liberty, many historians, architects and symbolists have pointed to intriguing similarities. Both monuments embody universal values: light, freedom, resistance to oppression and the power of a people.

The Colossus, erected in honor of Helios, Rhodes’ patron sun god, dominated the city as a symbol of victory and independence. The Statue of Liberty, donated by France to the United States in 1886, also represents a luminous figure holding a torch, welcoming newcomers as a promise of freedom and hope.

Both share a titanic dimension, a proud, upright posture, and a willingness to address the world beyond local borders. For some, the New York statue embodies a modern reinvention of the Rhodian myth, translating ancient ideals into contemporary, republican language.

Even if this affiliation remains symbolic rather than architectural, it bears witness to the Colossus’ lasting influence on world culture, well beyond the ancient Mediterranean.

Rhodes' strategic role in the age of the Colossus

Rhodes was not only renowned for its artistic influence and commercial prosperity: the island also played a central geopolitical role in the eastern Mediterranean. Situated at the crossroads of maritime routes linking Greece, Egypt, Asia Minor and the coasts of the Levant, it was a veritable crossroads of civilizations.

From the 4th century BC, Rhodes’ formidable fleet and organized port made it a naval power to be reckoned with. This mastery of the seas enabled the city to guarantee the security of trade and exercise a form of control over international shipping. What’s more, its school of diplomacy, strategic neutrality and judiciously forged alliances (notably with Rome and Lagid Egypt) enhanced its political prestige.

It was precisely this status as an influential player in the Hellenistic world that made the construction of the Colossus possible: more than just a religious tribute, the statue embodied the sovereignty, stability and grandeur of a city respected throughout the Mediterranean. Facing the world, the Colossus was as much a political statement as an artistic masterpiece.

An island at the crossroads of trade routes

Thanks to its strategic geographical position between the coasts of Asia Minor, the Peloponnese and the Nile delta in Egypt, Rhodes controlled several maritime routes essential to the economy of the Hellenistic world. Situated at the crossroads of trade between East and West, the island became an essential commercial hub from the 4th century BC onwards.

Its port, equipped with sophisticated quays and warehouses, saw the transit of a multitude of goods: Egyptian wheat, wine from the Levant, Greek oils, precious metals, timber, as well as spices, textiles and rare pigments. Rhodes played the role of intermediary, taxing cargo and guaranteeing the security of trade in the Aegean.

This logistical and economic mastery gave the city major political influence throughout the eastern Mediterranean. It played an active role in the balance between the great Hellenistic powers, such as the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria, while remaining independent. This exceptional dynamism contributed directly to the artistic and military boom that led to the erection of the Colossus, a veritable showcase of the city’s power.

A naval power feared throughout the Mediterranean

In the 3rd century BC, Rhodes possessed one of the most feared fleets in the Mediterranean basin. Comprising both merchant ships and triremes of war, it played a crucial role in the fight against piracy, which threatened the maritime routes between the Aegean Sea and the eastern Mediterranean.

The Rhodians, experts in navigation and naval strategy, established regular patrols to secure straits and trade routes. Their role as maritime policemen earned them the respect of the other Hellenistic powers, as well as that of Rome, which later entrusted them with the protection of certain areas.

This mastery of the seas enabled Rhodes to forge alliances with influential kingdoms such as the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Greek cities of Asia Minor. Thanks to its skilful diplomacy and naval strength, Rhodes became a key player in the geopolitical balances of the time.

The power of its fleet was not only defensive. It also guaranteed the free flow of goods, consolidating the city’s economic prosperity. This maritime and political context goes a long way to explaining why Rhodes was able to undertake such an ambitious project as the Colossus: a work to the glory of its strength, independence and naval prestige.

Strategic neutrality in the service of Hellenistic diplomacy

In addition to its maritime power, Rhodes enjoyed a unique political status in the Hellenistic world.. An independent city, it cultivated a position of active neutrality, enabling it to mediate in conflicts between the great powers of the time, notably the Ptolemies of Egypt, the Seleucids of Syria and the kingdoms of Macedonia.

Thanks to this reputation forbalance and political wisdom, Rhodes became a leading diplomatic center. Crucial negotiations were conducted here, reinforcing the island’s role as a geopolitical crossroads between East and West. The city’s internal stability, republican organization and renowned legal institutions made this diplomatic role all the more important.

The Colossus of Helios, erected following the victory over Demetrios Poliorcetes, was not only a monumental work of art. It also symbolized Rhodian unity, peace and resilience. Visible from afar, it proclaimed to the world that Rhodes was a haven of stability, neutrality and controlled power. This visual message further reinforced the island’s position on the political chessboard of the ancient Mediterranean.

Symbolic financing at the heart of a flourishing economy

The financing of the Colossus of Rhodes was not the result of simple patronage, but reflected the city’s political and economic intelligence. After the defeat of Demetrios Poliorcetes, the Rhodians recovered a colossal quantity of abandoned military equipment, including the famousHélépolis siege tower. This equipment was sold or melted down to finance a large part of the statue. This highly symbolic move transformed the remnants of war into a symbol of peace and resilience.

At the same time, port taxes levied on the many goods passing through the port of Rhodes, as well as diplomatic contributions and donations from allied cities, supplemented this funding. The island’s economic prosperity, fueled by a dense and secure maritime trade, enabled the city to generate substantial resources without jeopardizing its public finances.

This financing, both pragmatic and deeply symbolic, illustrates how Rhodes was able to convert its military victory and naval power into cultural and spiritual influence. The Colossus was not just a technical feat: it was the fruit of a political and economic model that was particularly advanced for its time.